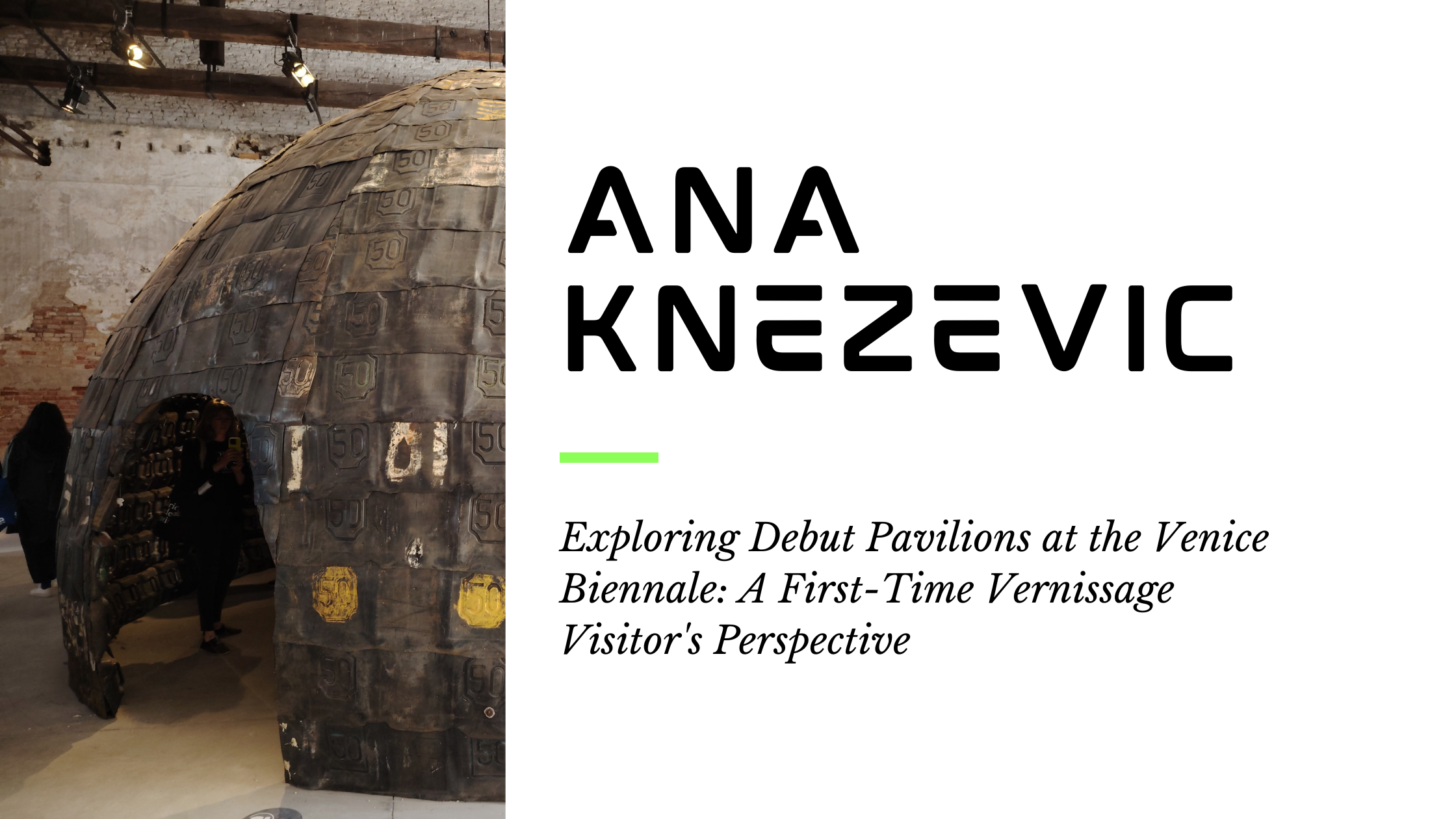

Exploring Debut Pavilions at the Venice Biennale: A First-Time Vernissage Visitor’s Perspective

In her latest review, Ana Knežević, a young art historian and curator at the Museum of African Art (MAU) in Belgrade, and a PhD student in museology and heritology, shares her inaugural visit to the Venice Biennale—a cornerstone event in the global art scene. For the first time, Ana explores the profound narratives embedded within three newly introduced African pavilions at the Biennale. Her analysis delves into the themes of migration, community, and contemporary issues as presented by Senegal, Benin, Ethiopia and other African showcases.

This review provides an exciting examination of the cultural narratives and artistic expressions that stood out during her visit, highlighting how these exhibitions contribute to a broader understanding of African art on the international stage. Through her eyes, readers gain insights into the dynamic interplay of heritage and innovation at one of the most celebrated art gatherings in the world.

As a young art historian, curator at the Museum of African Art in Belgrade and PhD student in museology and heritology at the Faculty of Philosophy in Belgrade, I visited the Venice Biennale for the first time in my life in 2024. It’s a strange feeling – thanks to your education, you are aware of the importance and significance of the event. You have read about the different pavilions and curators, you know the pavilions of your country and region, you have listened carefully to the stories of your friends and colleagues about previous editions, you have read critiques and reviews, but you have never experienced the visit yourself. Therefore, the room opens up to a whole specter of impressions: too crowded, too many queues, too much waiting, too much running, visiting too fast exhibitions and pavilions too quickly. Or, to make a long story short, to translate it into memes:

Meme published by freeze_magazine

Meme published by freeze_magazine

Even if it seems to be an unnecessary statement, from my point of view it is important to mention this insurmountability of the Biennale (during the vernissage and the time-limited visit) because it also has an impact on what is visited, what is seen, what is understood and in what way. At the invitation of my friends at I:BICA, and bearing in mind the above-mentioned conditions, I have decided to make a comment on 3 selected & first-ever African pavilions at the Venice Biennale and offer some further impressions and reflections on the exhibitions and pavilions I was able to visit. Although I had to walk through some parts of the Biennale and the exhibitions, there were also those precious and sacred moments of slowing down, immersing myself in the exhibition, talking and exchanging views with the artists and spending enough time in the exhibition space to make sense of and enjoy what was visible.

Senegalese Pavilion by Ana Knežević

Senegal

One of the “first” national pavilions at the Arsenale is that of Senegal, represented by Alioune Diagne and the exhibition Bokk – Bounds, curated by Massamba Mbaye. Diagne studied in Dakar and developed his unique technique of “unconscious signs” – small modules that come together to form a coherent figurative image. He also describes his artistic expression as “figure-abstro”, a complex, meticulous style of painting, forming figurative scenes with abstract elements inspired by calligraphy. The exhibition title Bokk- Bounds comes from the Wolof language and means “what is shared”, “held together“ and “family ties”. On the walls are puzzle-like paintings by Diagne, which are impressive both from above and from a distance. In the close-up view, we are immersed in the specific style of this artist and parts of sentences and statements “drown” in the canvas, while from a distance we perceive the juxtaposition of the depiction of migration, escalating poverty, resource depletion, racism, interdependence and contemporary disasters on the one hand and happy life scenes, education of children, the heritage of traditions and the sense of community on the other. Bokk – Bounds or “what is shared” as an artistic installation is completed by a traditional canoe wrapped in a textile made in Senegal, painted by the artist, to reflect on the history of humanity and the waves of migration responsible for an increasing separation from each other.

Senegalese Pavilion Detail 1 by Ana Knežević

Senegalese Pavilion Detail 1 by Ana Knežević

It is important to mention that the canoe is broken into 2 parts, which follows the diptych logic of the painting puzzle on the walls. Although the paintings are limited, you discover the experience of migration waves, poverty and racism with joie de vivre and social values “in a flow” or in a puzzle piece, while the broken canoe in communication with the large canvas opens up questions about the “future flow” of migrations, our mutual (mis)understanding, climate change and the position of heritage in today’s world. Among other things, this impressive exhibition with its memorable painting style also reminds me of the founding of the Museum of African Art in Belgrade and its almost half a century old permanent exhibition, which begins with a traditional canoe from Ghana and the saying “One Man, No Chop” or “One Man Cannot Survive Alone”, as well as the idea of the museum founders to emphasize the legacy of the Non-Aligned Movement and the politics of friendship in their legacy. When I bring these two canoes into conversation in my mind, I wonder if we are much more pessimistic and resigned today, or if we are more aware and realistic about future problems? The broken canoe definitely points to the shared experience that the whole exhibition is about, using tradition and heritage in the spirit of the times we live in.

Benin

Beninese Pavilion by Ana Knežević

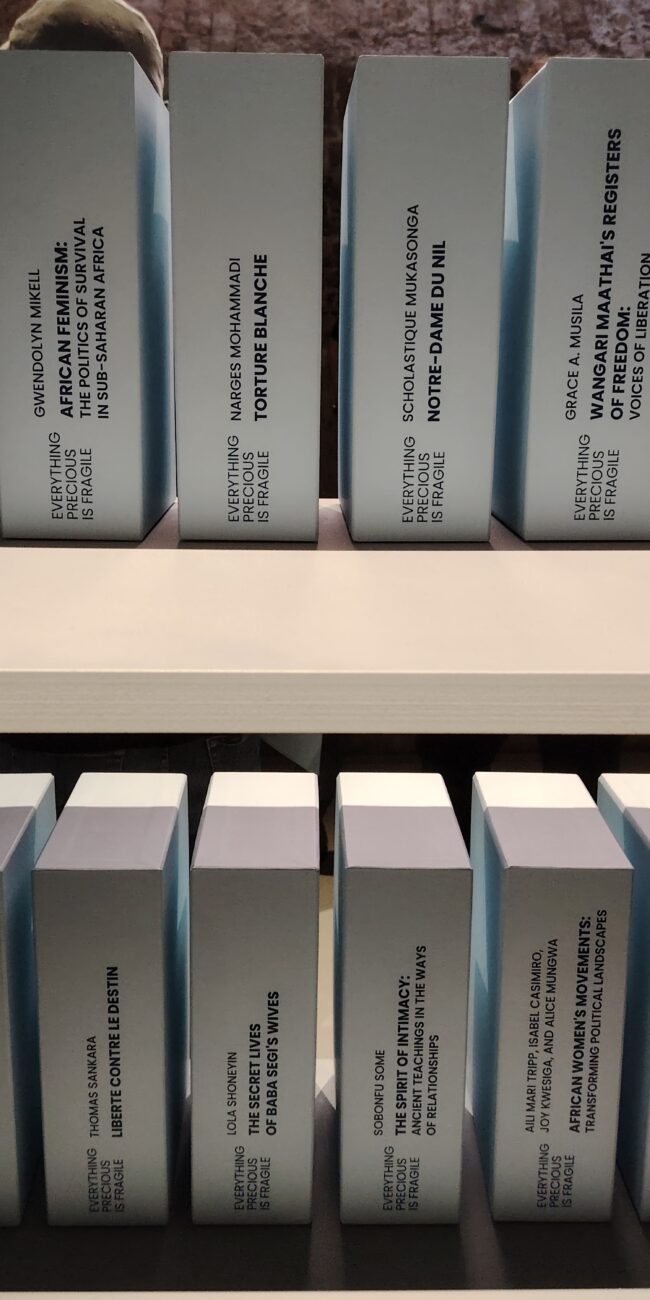

The concept of the pavilion’s curatorial team recognises the historical and ongoing epistemic injustices faced by indigenous knowledge systems and the erasure of feminist voices. “Eguè-lè-dé” is a rough translation of the idea of the fragility of an encased egg, translating the idea that “everything of value is fragile” – even the smallest things. I took advantage of the hectic moments of the Biennale and had the honour and opportunity to meet Moufouli Bello and Romuald Hazoumè at the Benin Pavilion. We had a short conversation about their works and about the Museum of African Art in Belgrade and exchanged exhibition materials and catalogues. In Bello’s installation you will find the “The Library of Resistance” and books titles reproductions,such as ”We should all be feminists” by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, “The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women Across The Ancient World” by Adrienne Mayor, “The Spirit of Intimacy: Ancient Teachings in The Ways of Relationships” by Sobonfu Some, etc. The installation highlights issues of feminism and female power with Bello’s evocative paintings, female portraits “Night Birds” inspired by the Gèlèdè practise and a ceremony with traditional and spiritual Yoruba Beninese dance focusing on motherhood. In Hazoumè’s installation entitled “Ashe”, which means “so be it” and “power” and which consists of his already recognisable cans, the visitor is “enveloped” by the circular lines of symbols, as the artist said, of all the people of Benin today, but also by figures of deportees, of Amazons, of spirits, of women. Hazoumè also told me that he had already exhibited in Belgrade as part of the 2018 October Salon, but he had not had the opportunity to visit the Museum of African Art. I hope that our short meeting at the Benin Pavilion will lead us to future collaborations and new conversations.

Bello Night Birds by Ana Knežević

The curatorial concept of the Benin Pavilion states: “For the past, they draw on the Gèlèdè philosophy as a narrative about the origins of our feminism; for the present, they draw inspiration from the struggles, confrontations and resistances that our daughters, mothers and women are currently waging in our cities, homes and businesses; for the future, they surprise us because the realm of possibilities is so vast that at the end of the road, feminism is no longer relegated to a category, but elevated to what it should be: a universal humanism.”

Bello Installation by Ana Knežević

Bello Library of Resistance by Ana Knežević

Ethiopia

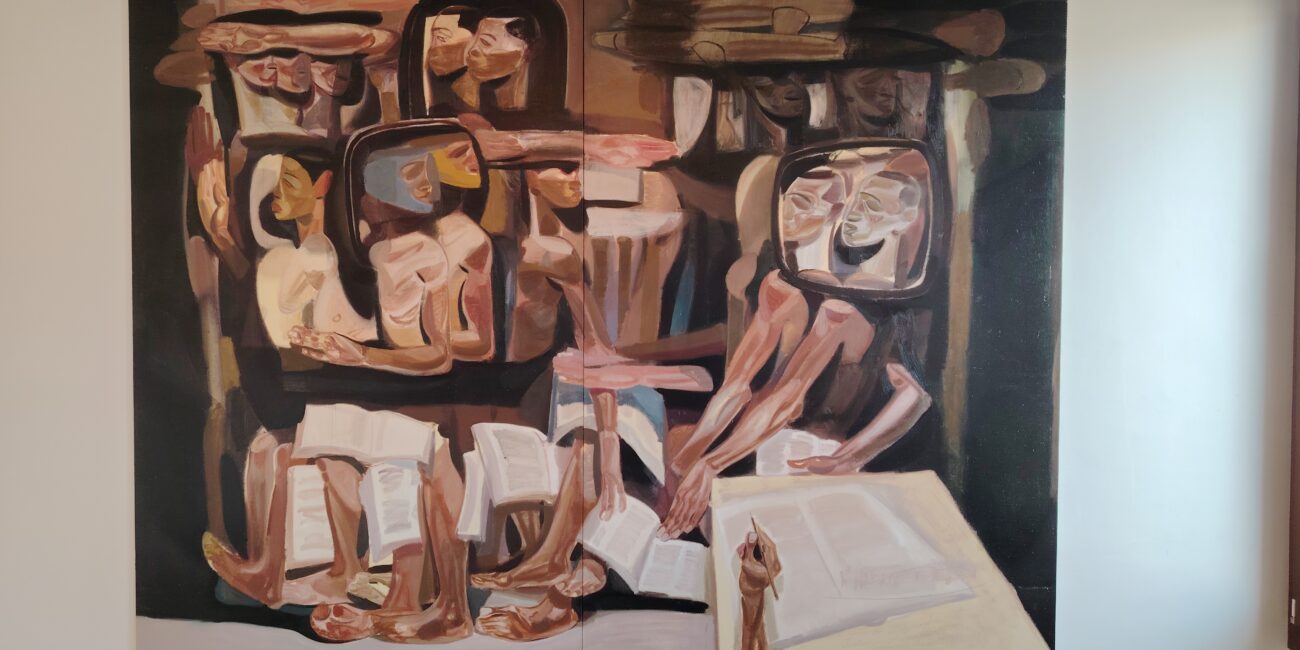

The Ethiopian Pavilion is also the first pavilion of the Venice Biennale and is located in Palazzo Bollani. It features a solo exhibition by Tesfaye Urgessa and is curated by Lemn Sissay, a poet, author and broadcaster. The exhibition, entitled “Prejudice and Belonging”, encompasses the experiences of Urgessa’s thirteen years studying in Germany. While visiting this pavilion, I had the opportunity to meet the artist, have a brief conversation and exchange the MAU and pavilion catalogues. In the catalogue of the very first Ethiopian pavilion, Urgessa explains: „People tend to think I am painting victims in my canvases, but it’s completely different. The figures hold all kinds of emotions, fragility as well as confidence. It is the figure presented without any judgement . It is saying: This is who I am, this is what I am!“

Ethiopian Pavilion by Ana Knežević

The pavilion’s catalogue contains reproductions of paintings, followed by a selection of verses from „Invisible Kisses“ by Lemn Sissay. Alongside the painting „No Country for Young Men“ (2024) the following verses are published:

„If there was ever one

who can offer you this and more;

Who in keyless rooms can open doors; Who in open doors can see open fields

and in open fields see harvests yield.“

The Ethiopian Pavilion offers an interesting experience through the work of this artist, who was born in 1983 and works in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Urgessa studied in Ethiopia with the modern master Tadesse Mesfin and later graduated from the Staatlichen Akademie in Stuttgart. Through these experiences, Urgessa was able to combine Ethiopian iconography and a deep fascination with traditional figurative painting to create a unique and striking language.

Since I started by saying that during the Venice Vernissage it is not possible to see (and especially not to really see and understand) not only all the pavilions and events, but only a part of them, I will of course conclude on this note. In this text, I have selected 3 African first exhibition pavilions for a description and a short commentary on impressions and reflections. Nonetheless, they are amazing artworks and African pavilions (just to name a few of them): Nigerian (Nigerian Imaginary, Palazzo Canal), Egyptian (Drama 1882, Giardini), Ivory Coast (The Blue Note, Centro Culturale Don Orione Artigianelli – Dorsoduro 947), South Africa (Quiet Ground, Arsenale), Seyshelly (PALA, Arsenale), Zimbabwe (Undone, Santa Maria della Pietà), DR Congo (Vibranium, IPAB Opere Riunite Buon Pastore), Uganda (Radiance: They dream In Time, Palazzo Palumbo Fossati), Cameroon (Nemo propheta in patria, Palazzo Donà delle Rose), the exhibition Passangers in Transit (Ex-Farmacia Solveni, Dorsoduro 993-994).

“Zambian Pavilion”

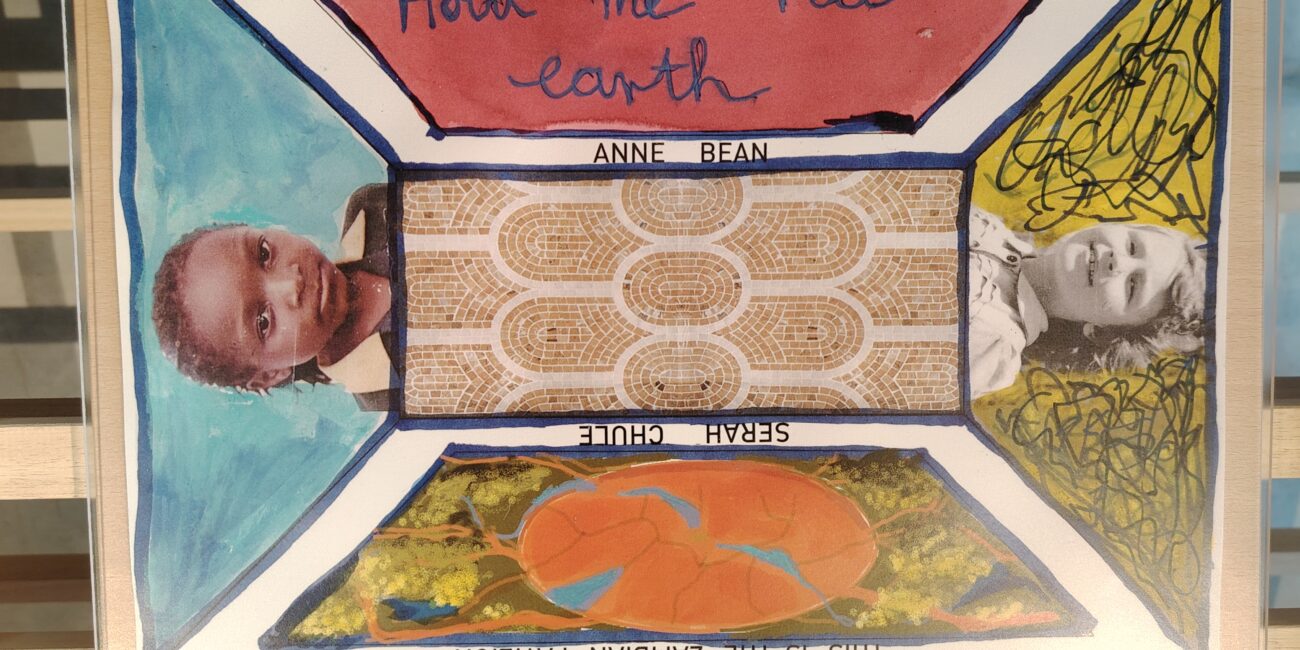

Finally, in addition to the African pavilions of the very first Venice Biennale that I was able to visit, I would like to mention another pavilion as a “never seen” African pavilion at the Venice Biennale, namely the “Zambian Pavilion”, i.e. the work of Anne Beam & Serah Chule, which was presented in the Croatian pavilion as part of what I would call the groundbreaking work of Vlatka Horvat “By the means at hand”, which brought a large number of small artworks to this pavilion, based on the forgotten but obviously still existing values of solidarity and collectivity. As I was one of the informal couriers of the Croatian pavilion and helped with the delivery of Vesna Pavlović‘s work, I enjoyed visiting this pavilion based on alternative art economies and I had the opportunity to see also one of the „never-seen“ pavilions at the Venice Biennale: the Zambian pavilion.

Zambian Pavilion from Croatian Pavilion by Ana Knežević

In conclusion, I would say that what could be seen in such a short time and in such a large crowd and hectic artworld is seen and reflected, in detail or in fragments. Perhaps the Venice Biennale, visited in its completeness, makes an extraordinary comment on the “strangers everywhere”. But in my experience it is an insurmountable art event with amazing artworks and pavilions, and I have commented here on just a few of them as points where I was able to enjoy the slowness of visiting the exhibition and the opportunities for meetings and conversations, especially with representatives of the African pavilions.

We extend our heartfelt thanks to Ana Knežević for her invaluable contribution to the I:BICA community through her unique, first of a kind review of the Venice Biennale. As an art historian, curator at the Museum of African Art in Belgrade, a PhD student in museology and heritology, and a dear friend of ours Ana brings a wealth of expertise and a unique academic perspective that helps us grasp the significant roles African pavilions play on the global stage.