Barbed Wires and Broad Horizons: Contemporary Land Art and the Boundaries of Ownership, Stewardship and Ecological Conservation

In our latest exploration, “Barbed Wires and Broad Horizons: Contemporary Land Art and the Boundaries of Ownership, Stewardship, and Ecological Conservation,” we delve into the fascinating world of Land Art from its postwar origins to its current form. Historically dominated by a ‘boys-club’ mindset, the genre, with iconic figures like Robert Smithson and Michael Heizer, is undergoing a transformative shift. We witness a departure from the grandiose displays of the past towards a more inclusive, nuanced approach by contemporary artists. This shift is not only about style but also a response to urgent climate concerns, redefining the genre’s engagement with the earth.

Central to our discussion is the shift in narrative and approach in Land Art, as we see artists challenging traditional notions of land ownership, stewardship, and ecological conservation. The transition from the monumental earthworks of the 20th century to more subtle, concept-driven practices reveals a genre evolving in response to contemporary issues like climate anxiety and the complexities of land rights. We also delve into how contemporary artists navigate the art market’s forces, juxtaposing commercialization with the need for genuine ecological engagement.

The postwar period of Land Art has historically been underscored by a boys-club-like canonization with its displays of mass and heroic gestures: think Robert Smithson, Michael Heizer, James Turrell. In 1970, the Polish collective Druga Grupa went so far as to satirize the hubris of their contemporaries by diligently documenting an earthworks piece that did, in fact, not exist. In the 1980’s, artists like Jody Pinto and Agnes Denes rejected the title of Land Artist, offering alternatives like “environmental art” or “your body in the land”, which could also include urban landscapes and playing with accessibility. In more recent years, the atomization of the genre has allowed contemporary artists to inquire, much more quietly, into a more humble approach.

Climate anxiety has ushered in a whole new urgency into the practice of Land Art. Earthworks has become less of a historical art period to be studied in school or artistically distanced from and instead a material reality that cannot be ignored. In more recent years, playing with the bureaucracy of land management as a tool has led to pieces intentionally utilizing commission sources and exhibition spaces and infusing their means of operating into the conceptualization of the piece itself – artists vary in their approach towards including or refusing the inevitable metabolizing forces of the art market. Broader Indigenous movements for decolonization, like Land Back, pose a question of the art industry’s moral viability in a world where systems of ownership, real estate or otherwise, remain critical for political and economic control. Conservation and stewardship may be hot button words, but contemporary artists are growing increasingly clear on their resolve in who must help them build these systems of care and how.

So, what differentiates contemporary land artists from their predecessors? Let’s start off with some romance, that little earthly thing we call love.

Druga Grupa, Giewont, actions at the foot of Giewont, 1970. From the left: Lesław Janicki, Wacław Janicki, Jacek Maria Stokłosa. Photo: Jacek Maria Stokłosa.

Druga Grupa, Jod [Iodine], happening at the Krzysztofory Gallery cafe, 1968. Photo: Wojciech Plewiński

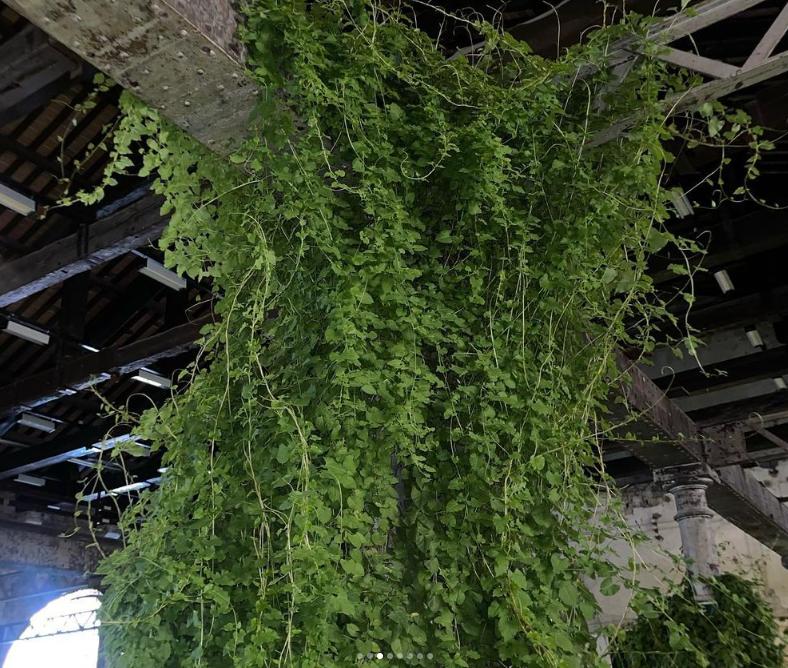

To See the Earth Before the End of the World, by artist Precious Okoyomon and was exhibited at the Venice Biennale in 2022, continued the 20th century device of bringing earthworks into the gallery space. Representing the United States, Okoyomon delivered a lush and immersive installation to the Biennale. Viewers were able to walk meandering paths through an indoor botanical landscape: sugar cane seemed to grow abundantly over the course of 7 months in the exhibition, along with bubbling streams of water, butterflies and kudzu, a plant the artist has confessed they have an “ongoing romance” with.

Kudzu, native to East Asia but invasive in North America, hangs over the space in its conspicuous veil, seeking swaths of light just as when it climbs up and over the forest edge buttressing American highways. Kudzu was initially introduced to the United States in Philadelphia’s 1876 World’s Fair and promoted as an innovative deterrent against soil erosion for the cotton industry in the south. That the Venice Biennale is modeled after the exposition format of the World Fairs seems to be a historical fact not lost on Okoyomon. Different organic entities bear names in the installation, acting as a summoning or charm into the space’s cosmology. In giving kudzu the name “resistance is an atmospheric condition”, the artist offers an invitation to shake off the plant’s ignoble reputation as either parasitic or a symptom of colonization. Detouring off of the footprints of artists like Walter De Maria, Okoyomon presents a walkable, soil-filled terrarium toeing the precipice of climate disruption and playfully nudging that nebulous anxiety. What is left is a frank pollination on the cusp of environmental crumbling, bare-faced and child-like in a devotional offering. In spite of colonial destruction, Okoyomon urges the viewer to embrace the earth that continues to nurture us.

In giving kudzu the name ‘resistance is an atmospheric condition’, the artist offers an invitation to shake off the plant’s ignoble reputation.

Photo by Precious Okoyomon/Instagram

Photo by Precious Okoyomon/Instagram

The Land Art movement of the 1960’s and 70’s planted itself firmly in the beginning stages of institutional critique, defiant against ideas of collection, ownership, and permanence. Oftentimes artists created these pieces with little regard for their preservation, as in the case with Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty and its near dissolution in the 1980’s. Organizations like the Dia Art Foundation or museums like Storm King are prominent safe havens for many major earthworks projects, which are kept in different capacities within their collections. While artists like Smithson made it logistically challenging, foundations like Dia Art have straddled murky legal and copyright solutions to owning the unownable, which extends not just into real estate territory but also with image rights of pieces like Spiral Jetty, located in Golden Spike National Park in Utah and in the collection since 1999. While being legal owners of the land and of the piece’s copyright, Smithson’s insistence on the works’ temporality do not make it protected under the United States Copyright Act. Because of this gray area, visitors are allowed to photograph the installation and disseminate these images themselves. Inevitably, questions arise: Does land ownership ultimately supersede an artist’s wishes for art conservation or a viewer’s right to own its image? Who does the art work and images belong to, if it is simultaneously owned and not owned by these organizations?

After a 20 year hiatus of acquiring new work, Dia Art recently added Cameron Rowland to their roster, an American conceptual artist who is known for using financial and legal systems as mediums to confront systemic racial injustice. This new project Depreciation, created jointly with the foundation in 2018, is a clear divergence from past accessions, most notably in their lack of use of the word “acquisition” in press releases at all. The Dia Foundation continues to instead now function – in their words – as an organization of stewardship. “The institution is implicated in our history of real estate. But our ways of working are not without their own critiques of Western expansion.” says Jordan Carter, a curator at Dia Arts.

After a 20 year hiatus of acquiring new work, Dia Art recently added Cameron Rowland to their roster, an American conceptual artist who is known for using financial and legal systems as mediums to confront systemic racial injustice.

The Dia Beacon building and surrounding landscape. | Rolf Müller – Own work| Photograph of the entrance to the Dia:Beacon Museum, United States of America | Wikipedia

Depreciation is a layered conceptual piece that exists around the legal trappings of land. Drawing from Union General Sherman’s Special Field Orders 15 proclamation, colloquially known as the “40 acres and a mule” rule to formerly enslaved people in the United states, the piece is an acre of land placed under a restrictive covenant by the artist. The property, located on Edisto Island in South Carolina and previously seized from formerly enslaved families places the land valuation at $0, which limits its development indefinitely. Visitation isn’t encouraged by the Dia Foundation, and artistically, doesn’t quite serve a purpose. The covenant exists between both the institution and the artist: while the land is technically not an acquisition by the Dia Foundation, they do maintain the overgrown property’s fees and associated film and video works put on exhibition. While many Land art pieces take time and resources to visit, some teetering on purely exclusionary like in the case of Michael Heizer’s “City”, Depreciation triangulates in a sort of ether between a land without a body, bureaucratic paperwork, and its reproduced images. Ecological conservation, in this instance, exists by its literal devaluation. Dia Art expresses a turning point in institutional awareness to turn towards more holistic approaches to supervising art and the land it lies on, but do their efforts go far enough to conduct true conservation?

A stand out example of art as sustainable practice is Sam Van Aken’s ongoing piece titled Tree of 40 Fruit, a work where the artist splices 40 different varieties of stone fruit onto a single tree. Van Aken modifies the grafts on these trees based on their location to include heirloom varieties historic to the area the work lives in. In Stanford’s collection, the multicolored tree produces apricots and almonds, a nod to the agricultural history of the Santa Clara valley. Long before the word “Silicon” was first uttered, the region was the world’s largest orchard fruit producer. In its New York City iteration, “Open Orchard”, visitors to the installation on Governors Island will be able to harvest the fruit, once the trees have matured. “Making a work about conservation would be one thing, making a work of conservation is another’,’ says Van Aken in an interview with Stanford.

How one tree grows 40 different kinds of fruit | Sam Van Aken | TED/YouTube

Artists are uniquely positioned to interrogate the boundaries of our lived experiences and natural sciences.

Many of these antique fruits had been passed down through families, but were lost due to agricultural monoculture: as soon as a fruit is deemed not hardy enough for industrial farming and shipping, it’s left forgotten. Orchard fruit varieties can only be propagated through asexual grafting, which renders growing from seeds mostly useless. Van Aken understands the necessity for passing down the knowledge of grafting as well as access to parent plants. “Open Orchard” provides educational seminars on cultivation in the free use space. In a Ted Talk presentation by the artist, he explains: “I received an email from the Department of Defense. The Defense Advanced Research Project Administration invited me to come talk about innovation and creativity, and it’s a conversation that quickly shifted to a discussion of food security”. Van Aken goes on to remark that he was once told that he had the largest collection of these heirloom and heritage fruits in the eastern United States, a fact of which he admits “as an artist, is absolutely terrifying.”

This joke, which garnered a good chuckle from the audience, is a poignant illumination on the potential in artists finding themselves in the uncertain and expanded field of ecological responsibility.

Artists are uniquely positioned to interrogate the boundaries of our lived experiences and natural sciences. Creatives who want to explore modes of care for the natural world in their work need support to build nurturing ecologies. What are the limitations of creating and maintaining work that aims to better connect us to the land in our world today, and how can we move past the limits that fail us?

If you have an interest in the growing relationship between Land Art and ecological conservation, follow us here to keep up with the broadening horizon between arts and science.

Sources:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tug7h7q5woY

https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-market-land-art-challenges-collecting-differently

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/04/arts/design/land-art-environment-groundswell-women.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/18/arts/design/women-land-artist-nasher-dallas.html

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uU2L5nTSHtc

https://www.samvanaken.com/tree-of-40-fruit-2

https://condenaststore.com/featured/hows-about-you-and-me-flying-out-to-utah-warren-miller.html

https://www.diaart.org/visit/visit-our-locations-sites/cameron-rowland-depreciation

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/19/arts/design/new-red-order-creative-time-queens-worlds-unfair.html

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ICBdCb_-elo

https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2023/05/18/cameron-rowland-dia-art-foundation-depreciation

https://condenaststore.com/featured/hows-about-you-and-me-flying-out-to-utah-warren-